On a sunny morning in Antarctica, I boarded a tandem kayak and headed for the highway.

Roughly 75 minutes later, after taking what was an intentionally circuitous route, my touring party of approximately 20 people arrived at our destination. Only this highway, at an Antarctic Peninsula landing site called Errera on Andvord Bay, had no asphalt, no striped lanes and no exhaust-emitting automobiles. Instead, as we kayakers watched from just a few yards offshore, dozens of gentoo penguins traversed its snowy lanes, making their way between the relative safety of a shoreside hill and the sea.

A few days earlier, Danny Johnston, the expedition leader of the Scenic Eclipse cruise ship I was sailing on, had informed passengers of these avian highways and had cautioned us not to walk across them so as not to disrupt the penguins as they move between nesting sites and the hunting grounds in the water.

Penguins have carved a network of trails, or highways at the Errera landing site on the Antarctic peninsula. Photo Credit: Robert Silk

Now here I was, seeing in person what to that point had struck me as a quirky, almost amusing, concept. Antarctic penguins really do have highways, it dawned on me, even if I think the pathways should more aptly be called penguin sidewalks, given their rather modest width and lack of vehicular traffic.

This particular penguin viewing was the culmination of my kayak trip that morning, an excursion that was included in the sailing price. But it was far from the lone highlight. After experiencing predominantly cloudy weather during my first three days exploring Antarctica by land and sea as a hosted guest aboard the Eclipse, the morning fog on this day had lifted just before my group hit the water for an approximately two-hour paddle. The deep-blue skies that followed offered clean vistas of the surrounding glaciers and snowcapped peaks.

The flat water was another pleasure, especially after wind and waves had forced the Eclipse team to alter and delay the excursion itinerary the previous day as the ship sought sheltered conditions.

Related Dispatches:

For 15 years, while I lived in the Florida Keys, I paddled regularly through the bays and waterways that make up the southern portion of the Everglades ecosystem. On this day, despite the markedly different scenery and temperature, the calm water reminded me of the conditions that were so common in my former Florida home.

We paddled the bay leisurely, carefully navigating around ever-present chunks of floating ice and pausing frequently for photos or to simply experience the moment. Only the periodic noise from the Eclipse’s helicopter tours, especially during the early portion of the paddle, disrupted the tranquility.

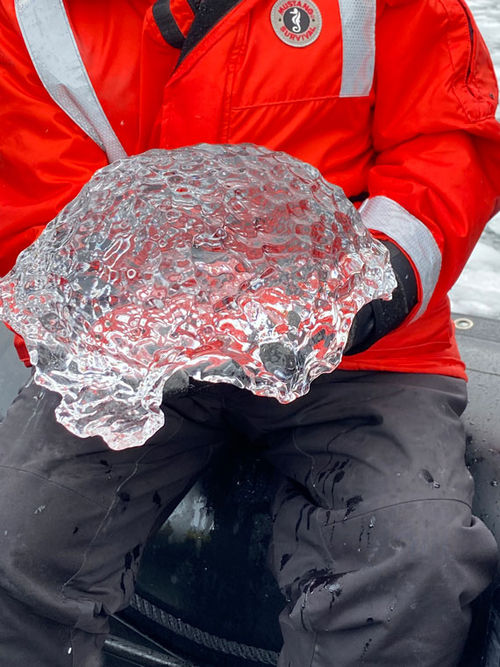

The crystal-like appearance of this ice block is evidence that it is thousands of years old. Photo Credit: Robert Silk

About that ice: It doesn’t get the headlines that the continent’s penguins, seals and whales do. But, at least for me, it’s almost as fascinating. Positioned in a kayak, so close to the surface of the water, it is especially easy to see how distinct each ice block is. Texture, color, shape and size all vary, just like the full-size icebergs. On one occasion during my trip, guide Sean Bodden grabbed a football-size block of ice from the water that looked as clear and beautiful as a crystal. Its clarity, he explained, is evidence that the ice block is thousands of years old. Over time, the weight of the ice has squeezed out all the oxygen.

Conversely, the stunningly deep-blue icebergs that can occasionally be seen here have that color because they have only newly broken off a glacier and therefore snow and temperature changes haven’t yet had time to turn them white.

The wonders of Antarctica with Scenic Cruises

During this morning paddle, penguins were my prize animal sighting, although a few other people on the excursion caught a glimpse of an Antarctic minke whale. The penguins, though, weren’t only at the Errera landing site. They could also be seen swimming through the water in the style of porpoises, a technique that I’ve come to learn is in fact known as “porpoising.”

Fur seals like this one are just some of the wildlife an Antarctic kayaker could spot. Photo Credit: Robert Silk

Other kayak or stand-up paddleboard excursions during the course of this 11-day sailing of the Eclipse had yielded multiple whale sightings as well as long looks at seals of various species resting on sea ice.

As my kayaking tour wound down, though, it was the penguins on those highways that earned my rapt attention. At times, the birds waddled in small groups to a point on the rocks, then dove together for a short bath, before reemerging, also in unison, to clumsily climb out of the water. Other penguins traversed the highway seemingly headed for a swim, before changing their minds and turning around.

The Antarctic sun warming our faces (seriously), we sat roughly in place for maybe 20 minutes watching this wonderful scene before returning to the ship. But as the guides began loading paddlers into the waiting Zodiac boat that would ferry us there, I made sure my kayak was last. I just wanted to enjoy those few extra moments on the water.